|

| Professor Jane Naana Opoku-Agyemang the Minister of Education, advocates the use of the mother tongue as a medium of instruction in schools |

Let us begin by asserting the undeniable link between socio-economic development and quality education and, by so doing, establish the corollary that the lack of quality education leads to poverty. Now, it has been proved in every society, nation and clime that quality education is largely dependent on the medium of instruction.

Research has also been conclusive on the fact that those with a solid mastery of their mother tongue (termed L1) are not only better at mastering a second language (L2) which, in our case is English (cf the great African writers – Soyinka, Achebe, Awoonor, Armah, Anyidoho, Ngugi, etc.), but also better at understanding concepts in science, mathematics, philosophy, etc. The point here is that with a firm grounding in the mother tongue, the child has a cognitive reference point on which to build all subsequent learning processes.

It is for this reason that almost all formerly colonised countries outside Africa (with the exception of settler nations such as USA, Canada, Australia and Latin-American nations) use their national (indigenous) language (s) as the medium of instruction, adopting various formulas or arrangements as they deem appropriate and developing programmes for the study of the relevant foreign language (s) for regional and global integration. Such is the case with China, India, Vietnam, Laos, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, etc., countries which, undeniably, have chalked up considerable development successes.

Exhaustive studies

In Africa, there are a few success stories such as Burundi, Rwanda and Madagascar, but in most countries, and especially here in Ghana, we are still grappling with the language policy issue, though having adopted a specific language policy, we should consider the debate over and concentrate on proper planning, execution and monitoring. I believe this is because a large number of decision makers and commentators are either ignorant of the exhaustive studies already done and the details of Ghana’s current language policy, or simply wasting our time, shouting from the rooftop.

For example, Kofi Akordor’s concerns over the multiplicity of languages and dialects are centuries late. Dialectal, regional, even occupational and group differences are a constant in any language scenario. There is a concept called language standardisation which applies to all languages adopted as a national or regional language, be it in the so-called developed nations or in the developing ones.

It is a process by which stakeholders settle on a particular variant of the said language, with a number of dialectal accommodations, which then becomes the standard language. This has already been done in most of the Ghanaian indigenous languages - Akan (Fante and Twi), Nzema, Ga, Ga-Adangbe, Ewe, Gonja, Kasem, Dagbani, and Dagaare. As a matter of fact, it began with the Christian missionaries’ translations of the Bible into the Ghanaian languages and language programmes for purposes of proselytism, and it was on the basis of this standardisation that these languages have been used in schools and taught as undergraduate and sometimes postgraduate courses in the University of Ghana, Legon, University of Cape Coast and especially in the University of Education, Winneba.

Yes, the multiplicity of indigenous languages in Ghana poses a challenge, but for which ample studies and proposals have been made, waiting for implementation, especially with regard to the urban centres where there is a concentration of this multiplicity of ethnic origins.

It is pertinent, at this point, to remind our readers that contrary to what Mr Akordor thinks, the language scenario in the USA is not at all homogeneous and smooth. All the language nationalities there (notably the Hispanic) are in various ways vindicating a presence and visibility. So it is in France (Breton and Basque), Spain (Basque and Catalan) and Belgium (Wallon and Flemish).

Native language as medium of instruction

It is also necessary to point out that all the prosperous nations mentioned by Mr Akordor use as their medium of instruction, at least at the initial stage, a language which is native to the majority of their inhabitants, not a foreign language.

How do we get government policies and development programmes understood and bought into by our people if we cannot communicate with them in our native languages? How can we communicate with them in our native languages if most of those manning our institutions, products of our school system, are not proficient in their mother tongues? Just listen to any attempt at radio or TV discussion in any of our local languages and calculate the percentage of English expressions. Neither is the quality of our performance of English, in most cases, anything to write home about. Heads we lose, tails we lose! With this situation, how can we develop? This, I believe, is the point the Minister was putting across.

Again, let it be stressed that this is not about rivalry between our native languages and English, or any other foreign language. As Mr Akordor correctly stated, the Germans, French, Spaniards, Portuguese, etc., are learning English, but not as a hidden secret; it is for regional and global integration, especially within the context of the European Union. Are we Ghanaians learning French, as our official language policy stipulates, to integrate properly into ECOWAS?

The failure to eradicate poverty does not reside in the axiomatic expressions being ridiculed by Mr Akordor, but in our inability to read up on issues and take necessary steps to implement policies we have signed up to. Our indigenous languages do not deserve the patronising “Local languages must not die” assurance. They are the source of our identity, strength, pride and cosmovision. They hold the key to our development.

The writer is with the Ghana Institute of Languages, Accra

amuzu22@yahoo.com

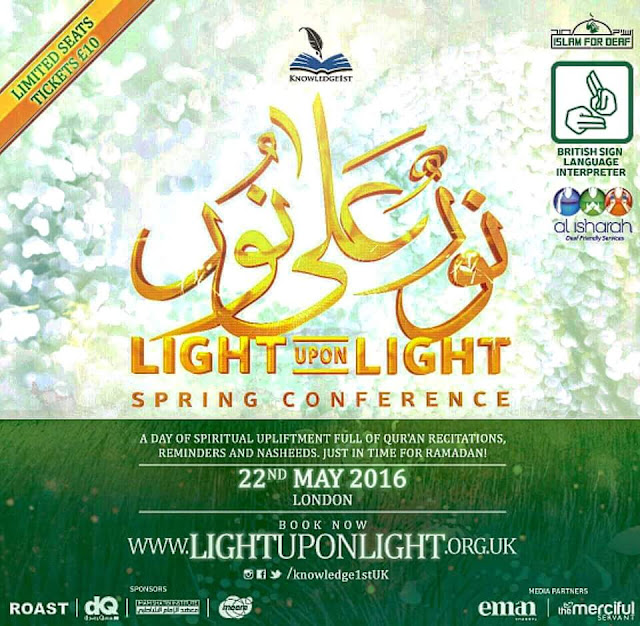

Advertisement Banner

No comments:

Post a Comment